article by

Adam Bruce

|

July 14th, 2008 | reader rating: 7 |

|

|

There is not a fan of classical music in the world who does not know what composer is, or more specifically, what their job is. But beyond this mundane definition lies a more profound debate within the compositional community, which is asking one question: “What is the modern composer?” It is with no doubt that this is at least partly due to the turbulent history of the composer in society, but this doesn’t explain it completely. Personally, as a composer and a listener, I have long thought about this single question, keeping it in my mind for almost six months now, and in that space of time I have reached several conclusions. It is those which I share with you now.

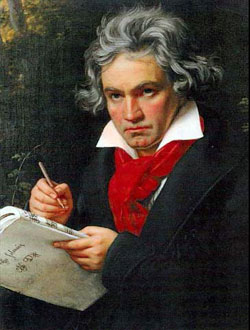

Beethoven’s Fifth and Sixth symphonies characterized the beginning of the Romantic Period

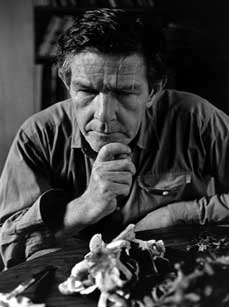

Besides the changes in patrons over the years we’ve also had some changes to society, and how it views us. You see, from the Renaissance era to the late Classical era (or about 1400-1800 for those of you year people), we were seen primarily as craftspeople. Like the wood carver, or the blacksmith, or the hat maker, we were the same as everyone else. This issue deeply affected the way music was both written and perceived by the public. Music as a craft was different than its later forms because it was a craft. What is a craft? The short answer is that a craft is an endeavor which follows basic rules of creation to achieve and end result, the rules for the music “craft” being those of music theory, which is for all intents and purposes, a set of principles or rules for creating decent (not great mind you, but decant) music. The casual listener may at least think of the names of some branches of music theory such as Counterpoint sound familiar, and it is these things that go in, along with a little creativity, to the composition of classical music. In using these rules of music theory in all compositions as absolute guidelines the composers of these periods, with a few exceptions, were creating in the medium of a craft.  The modernist John Cage, composer of music such as 2:33 of silence

Things all changed by the Romantic period, composers such as Beethoven in particular made music composition in to something it had never been before: an art. What makes art different from craft? Art is different because it does not rely on preset rules for its creation. The slow but existent departure from music theory created many new and creative thoughts in the compositional minds of the Romantic era and onwards. There was the creation of new forms. Some composers used music to describe the outside world in a way which hadn’t been previously done, and many were even just realizing that it was a free medium. This departure from theory had many good effects on music, but as well as the good, there were those who wanted to take things to the extremes, which would lead many to ask the question “what is the difference between music and noise?” in the oncoming century.

The 20th century brought many respectable things, such as Stravinskian atonalism, and the early avante garde music, like Rachmaninov for the Russians, and Copland for the Americans. There was trouble on the horizon though, and its name was John Cage. I sincerely believe that no sane person enjoys his music to the same effect as say Beethoven’s fifth piano concerto. To me Cage and his whole armada of music-radicals were signifying the doom of the avante garde movement, which had began in such a good way, and I even hold it as my opinion that they caused the public to lose interest in classical music altogether after a short period of interest in the Cagian style, which was more for the novelty than for the art. It seemed as if they didn’t compose, but merely made fun of composing which is why I would not consider him a true composer, at least to the level of the romantics, and early avant-gardists, and it is unfortunate, in my opinion, that the academia does.

So I think we composers are at a crossroads. We seek the gentle balance between artistic deviance and complete anarchy, and in that process have reached no Rosetta Stone. I personally try to incorporate music theory in to my own compositions, but not to the point that it hinders my creative process. It seems a little self-centered to say that this is what every composer to do, but I can’t help but think that some version of this is what will reclaim the contemporary classical genre in the eyes and ears of the listeners. I think that the composers might benefit from listening to their own music, and this in a nutshell is what I believe a music composer should be: the person who is qualified to listen to their own music. And so if we can learn to compose what we ourselves enjoy, then you, the listeners, might start to want to begin listening again, and the word modern may lose how synonymous it is with the word toxic. Slowly then, over time, we can make some steps toward reclaiming music composition for our own again, and that, my friends, is music to my ears.

The contents, views and opinions in this article are those of its author.

|

|

User comments:

|

Wow! so composer is a craftspeople, music is a craft, wonderful Wow! so composer is a craftspeople, music is a craft, wonderful |

Posted by sam on April 17th, 2009 @ 6:22 am GMT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|